Work Life Balance?

How You're Wired May Have Something To Do With It

By: Ryan Malone

Published: 12/05/2019

For Professional Engineer Contuing Education Credits Click Here

Original article found at Zapier

Work-life balance—or work-life integration—is a hot topic right now. There are dozens of articles published every week about it, and everyone has their own opinions on how to achieve it. Even employers are getting in on the trend, presenting work-life balance as a perk in job descriptions.

There are certainly ways that the company you work for can destroy your work-life balance, hustle culture being a prime example. But there's also research that suggests that achieving work-life balance has little to do with your job—it's mostly driven by your personality.

First, Let's Agree That Work-Life Balance Is Difficult to Define

In a 2014 study on work-life balance policies in the workplace, researchers Diana Benito-Osorio, Laura Muñoz-Aguado, and Cristina Villar reviewed all of the ways work-life balance has been defined in various research studies. They found 37 different definitions in studies conducted over 20 years.

Some of the definitions focus on the amount of time spent in each activity ("Work-life balance refers to the individual capacity to properly manage personal and professional life"). Some refer to an individual's goals and priorities ("Work-life balance is about effectively managing the juggling act between paid work and all other activities that are important to people, such as family, community activities, voluntary works, personal development, and leisure and recreation"). And some refer more to an individual's mental state when at work or home ("Work-life balance is the extent to which an individual is equally engaged in his or her work role and family life")

So for some people, work-life balance means having an equal amount of time allocated to both work and non-work activities. For others, it means distancing themselves from thoughts about work so that they're able to be fully engaged in activities outside of work. In this piece, we're going to focus primarily on the latter definition.

Of course, there are situations where an imbalance between work and life is directly caused by your job—for example, if you're working 16-hour days to make partner at your law firm, you're an on-call surgeon, or you have a boss who expects you always to be online. But when it's not directly related to work expectations, an inability to achieve work-life balance may be an outcome of your personality.

How Personality Impacts Your Ability to Achieve Work-Life Balance

In her book Home and Work: Negotiating Boundaries through Everyday Life, sociologist Christena Nippert-Eng proposes that there are two types of people:

- Segmentors are people who are able to draw clear lines between work and life. Segregating work and life into separate sections of their minds is as natural as breathing.

- Integrators are people who struggle to separate work and life. They think about life at work and work at home and are much more likely to work—and think about work—during off hours.

If we go back to our definitions of work-life balance, Segmentors may be able to work more than 40 hours a week and still feel like they have sufficient work-life balance because they can shut off thoughts about work when they go home.

Integrators, on the other hand, may struggle even at 40 hours a week because they continue to think about work at home, making them less engaged with their families, priorities, and activities outside of work. Or they may be more prone to work outside of work hours, limiting the amount of time they have for personal activities and priorities.

So if you're an Integrator, your job, boss, or employer may have little to do with your inability to achieve work-life balance. It may simply be that you're inclined to blur the lines—incapable of segmenting the different parts of your life—so your struggle to achieve work-life balance follows you from job to job throughout your entire career.

Most People Are Integrators

A few years ago, the People Analytics team at Google sought to understand how Nippert-Eng's findings applied to Google employees. They conducted a study and found that only 31 percent of their employees could be classified as Segmentors.

The other 69 percent—more than two-thirds of all of their employees—were Integrators.

Additionally, they found that Segmentors tended to be much more satisfied with their well-being than Integrators. Integrators, on the other hand, were much more likely to express their desire to find a better balance between work and life.

If you feel like you struggle to balance work and life, you're probably an Integrator. And unless you work for someone like Elon Musk who believes everyone should be working 80 hours a week, those emails you're reading and sending outside of work are signs that you need to make an effort to create a better work-life balance for yourself.

Achieving Work-Life Balance as an Integrator

Without a doubt, I am an Integrator. A few years ago, I worked with a Segregator—let's call him Frank—in a particularly stressful job. One morning, I was chatting with Frank about our project while we were getting ready for a meeting, and I mentioned that I had trouble sleeping the night before because I couldn't stop thinking about a new problem we were facing on the project.

"You were up late thinking about work?" Frank asked.

"Yes," I said. "You weren't?"

"I never think about work after I leave here for the day," he replied.

I didn't believe him—not for a second. "Just stop thinking about work" is something many people have recommended to me over the years, something that seems as silly as saying "just don't feel hungry." So I assumed Frank was lying or exaggerating.

As it turns out, Frank was a Segregator.

But when you're an Integrator, the idea of just not thinking about work at home sounds like a fairy tale. You've probably gotten some of the same advice I have over the years—"try meditating" being the core recommendation. Once, someone told me to imagine I was lying on a cloud, and every time I had a thought, put it in a box and throw it off the cloud.

I spent 15 minutes throwing boxes like I was a package sorter at UPS before finally calling it quits.

"Just don't think about it" simply isn't a viable solution to finding a better work-life balance; it's not a viable solution to anything, really. It's as helpful as telling an anxious person not to worry.

However, there is some research that may hold the keys to overcoming your Integrator tendencies so that you can train yourself to be more like Frank.

Find an activity that frees your mind from thoughts about work

A study by Sabine Sonnentag and Charlotte Fritz published in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology presents research showing that drawing a line between work and life requires psychological detachment.

When we're at work, we experience work-related stress. Once that stress is no longer present, our bodies and brains begin to recover. But Sonnentag and Fritz argue that simply being away from work isn't enough to fully recover; you also need to create psychological detachment from work. In other words, to recover from work, you have to stop thinking about work.

So yes, we're back to "just stop thinking about it," but their research offers some actionable strategies. They found that engaging in activities outside of work, from simple things like taking a walk or reading a book to more intensive activities like learning a language or playing a sport—were much more likely to help people detach from work and work-related thoughts.

But the specific activity that creates psychological detachment differs from person to person. "It is not a specific activity per se that helps to recover from job stress but its underlying attributes such as relaxation or psychological distance from job-related issues," Sonnentag and Fritz write.

To find your activity, you may have to try different things to see what works. After work, go for a jog, cook dinner, or take a class on a subject you're interested in, and see which activity frees your mind from work and makes you feel more recovered from work stress.

If you go for a jog after work but think about work the whole time you're jogging, that's probably not the right activity for you. Find one that fully takes your mind away from work thoughts.

If you can find a way to create the psychological detachment you need to recover, you may find it much easier to create the work-life balance you desire.

Stop engaging in activities that remind you of work

Another work-life balance definition listed in the Benito-Osorio, Muñoz-Aguado, and Villar study references the changing nature of work as a factor in our inability to find balance: "Personal control of time focused at the individual or family level for those who have difficulty finding time for personal life because of the encompassing nature of many contemporary forms of work."

Why is contemporary work all-encompassing? A big reason is that we have access to work all the time thanks to laptops and mobile phones. Many of us use the same device for both personal and professional tasks and communications—although maybe we shouldn't—making it difficult to avoid reminders of work while away from work.

Have you ever glanced at your phone just before bed, noticed an unread email, read said email, and spent the next several hours stressing over its contents? Have you ever done the same first thing in the morning, after dinner, or while killing time over the weekend?

If so, there's an easy way to create a better work-life balance for yourself: Stop doing that.

Another important aspect of recovery is avoiding continued exposure to the cause of your stress. As Sonnentag and Fritz write: "it is an important precondition for recovery that the functional systems taxed during work will not be called upon any longer." In other words, every time you check in on work when you're not supposed to be working, you're inhibiting your ability to relax, recover, and detach from work.

When Google's Dublin office made employees drop their devices off at the end of the day so they couldn't work at home, many people reported feeling much less stressed. But even if your employer doesn't pry your devices from your hands as you leave work, there are ways to keep yourself from checking in on work at home.

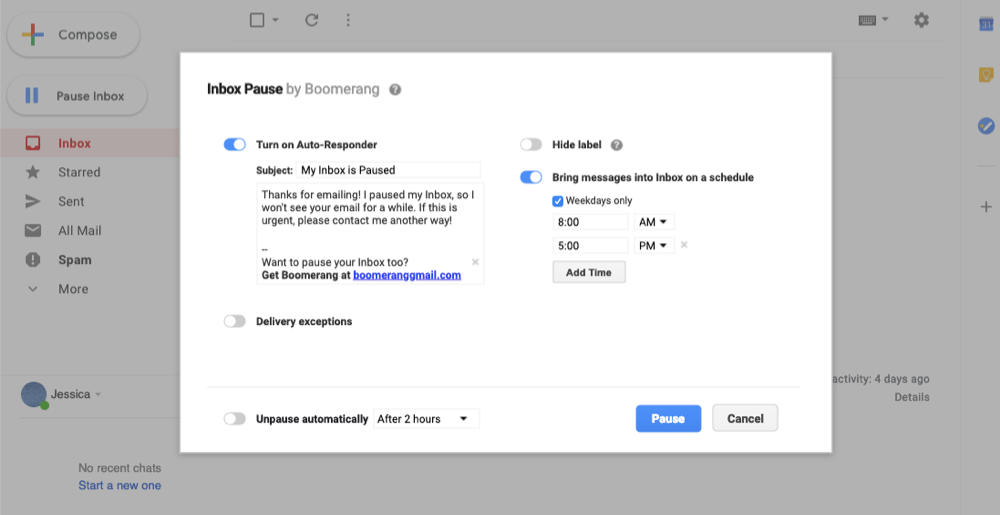

Boomerang—a free Gmail and Outlook extension—offers a feature called Inbox Pause that lets you create a schedule for when you want to receive email. If you don't want to be tempted to read work emails in the evenings and on weekends, just create a schedule in Boomerang to have your email delivered only during working hours.

The fact that it doesn't deliver your email is key because it means you won't see new emails even if you're tempted to check your inbox in the evening.

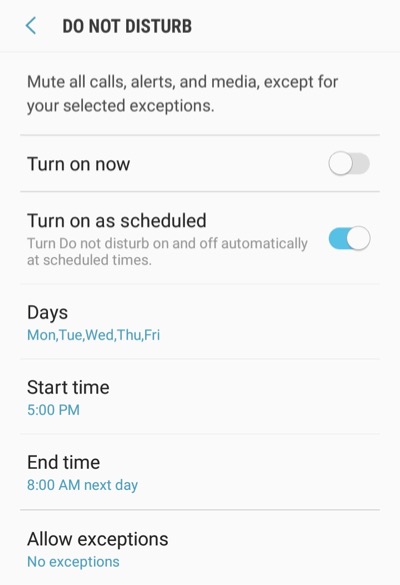

If calls and texts on your work phone are a problem, you can use your phone's do not disturb feature to set a schedule for when you want all incoming notifications to be silenced.

If it's Slack that draws you back into work, you can set up a do-not-disturb schedule there, too.

These things all reduce the likelihood of being tempted to check in on work while you're off, but in the end, it mostly boils down to changing your behavior. If you're tempted to check in on work over the weekend, you have to avoid the temptation, knowing your future work-life-balanced self will thank you for it.

Talk to your boss about your personal goals

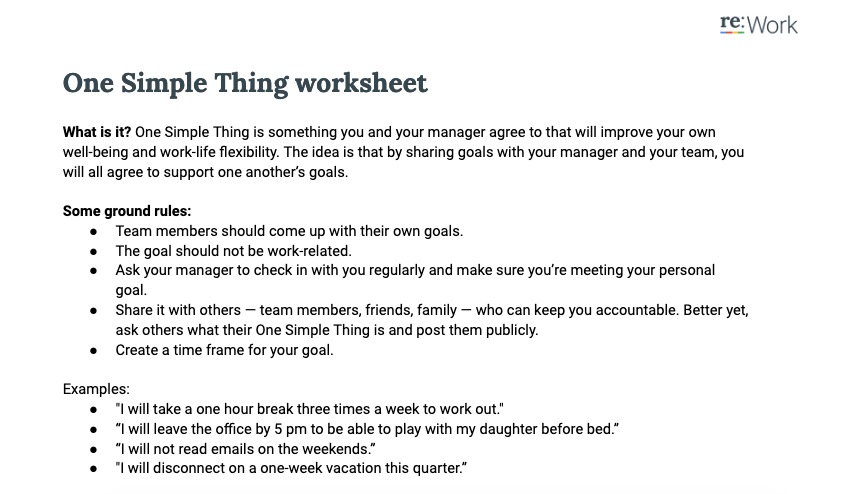

Google's People Analytics team recommends another strategy they call the "One Simple Thing" goal-setting technique. An employee shares a personal goal—something like "I won't read work emails at home"—with their boss. The employee's boss then becomes accountable for holding the employee to that goal.

And while Google's People Analytics team says they haven't been able to measure the success of the technique, other studies show that sharing personal goals with your boss can be beneficial for both you and the company you work for.

In an article for Harvard Business Review, executive coach Michael E. Kibler describes the results of a year-long executive development program focused on "active partnering"—a system where executives share both personal and professional goals with their bosses. Together, the two parties form strategies for how the organization can help support those goals.

Upon entering the program, 60 of the 473 participating executives noted that they were either considering leaving their firms or actively looking for new jobs. But in the five years after participating in the program, only two of the executives actually left their jobs.

The idea of sharing your personal goals—and your efforts to achieve work-life balance—with your boss may sound like an uncomfortable and unprofessional conversation, but there's value in having it. Your boss may be able to support you in your efforts to leave work at work by holding you accountable for working on the weekends, helping you identify tasks you really shouldn't be completing, or assisting you in brainstorming ways to delegate and share your workload.

And if your boss isn't on board with helping you achieve your goals, it may be a sign that it's not just your personality that's creating your work-life imbalance. It might be time to look for a new job.

If you are the boss, Google's "One Simple Thing" approach may be a good exercise to do with your team to help your employees better balance work and life. You can even make a copy of Google's template for the exercise as a simple starting point.

Make a to-do list for tomorrow at the end of every day

In his book The Organized Mind, neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin explains that when we're trying to remember something, our brains put that information into a "rehearsal loop" that seeks to regularly remind us of that task.

If you leave work for the day with a brain full of tasks that you need to complete tomorrow or next week, your brain will constantly cycle back to those tasks while you're away from work. And since part of psychological detachment requires that we distance ourselves from thoughts about work, that rehearsal loop works against our ability to achieve work-life balance.

One strategy for closing the rehearsal loop and leaving work tasks at work: Spend 5-15 minutes at the end of every day writing down the things you need to work on the next day and/or week. Even something as simple as adding tasks to a list in a to-do app can help you leave your thoughts about those tasks behind. But there's also evidence that writing a more detailed and reflective journal entry could be worthwhile, too.

Social psychologist James W. Pennebaker says that "keeping a journal helps to organize an event in our mind. When we do that, our working memory improves, since our brains are freed from the enormously taxing job of processing that experience."

So by taking time at the end of your workday to reflect on the day's events, process and order those events in your mind, and write down what you need to take care of the next time you're at work, you can essentially empty your mind of thoughts about work before you head home for the day.

If you don't already have an established method for documenting your to-dos, consider these eight different task management methods to find the approach that works for you.

Integrators Who Work From Home

When you work in an office, commuting serves as an everyday event that creates a separation between work time and home time. But for those of us who work from home, there may not be such a clear distinction. The difference between working and relaxing may be as minuscule as shutting your laptop and grabbing a TV remote.

In 2004, researchers Tracey Crosbie and Jeanne Moore published the results of their study investigating whether working from home was the solution to achieving work-life balance. Their conclusion: more research was needed.

While some people expressed having a better work-life balance while working from home, others expressed that the balance had degraded since working from home.

Some of the participants said that working from home made them feel like they had more time to spend with their children—even if they were working longer hours. Most said working from home gave them more flexibility and control over how they spend their time.

Others expressed frustration at having to look at their work equipment and supplies while at home or said that getting work calls and direct mail at home caused tension within their families.

The researchers' conclusion: "Those who are thinking of working from home should give careful consideration to their personality, skills, and aspirations. For example, those who tend to work long hours outside of the home might find that home life is even further marginalized by work life."

For an Integrator who's already prone to blurring the lines between work and life, working from home can exacerbate that tendency, so it's important to set clear lines between work and life:

- Try setting working hours and sticking to them, much in the way that you would do if you were expected to be in the office from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

- Create a space for your work that's separate from your living space. If you work on the couch and relax on the couch, there's no distinction between the two different activities.

- Consider the benefits of signing up for a coworking space to take your work outside of the house—or try working from a coffee shop occasionally.

But none of that is to say that working from home is inherently bad for work-life balance. Many of the study's participants said that working from home gave them more control over their personal time, which Sonnentag and Fritz say is another factor that enhances our ability to recover from work.

Achieving Work-Life Balance When It's Not in Your Nature to Do So

Sometimes, there's a clear reason why you haven't achieved a balance between work and life. If your job requires you to travel constantly, your boss demands that you work overtime regularly, or you're forced to work multiple jobs to make ends meet, those are obvious causes of your work-life imbalance.

But if those things aren't the case, it may just be in your nature to blur the lines between work and life. No job or career change can fix that for you. Instead, you have to make a focused effort to mimic Segregators—to draw clear lines between work life and home life—so your body and brain can relax, recover, and create more psychological distance between the two activities.